Jake Sulpice

☆ Come and See

Watched on December 2, 2023

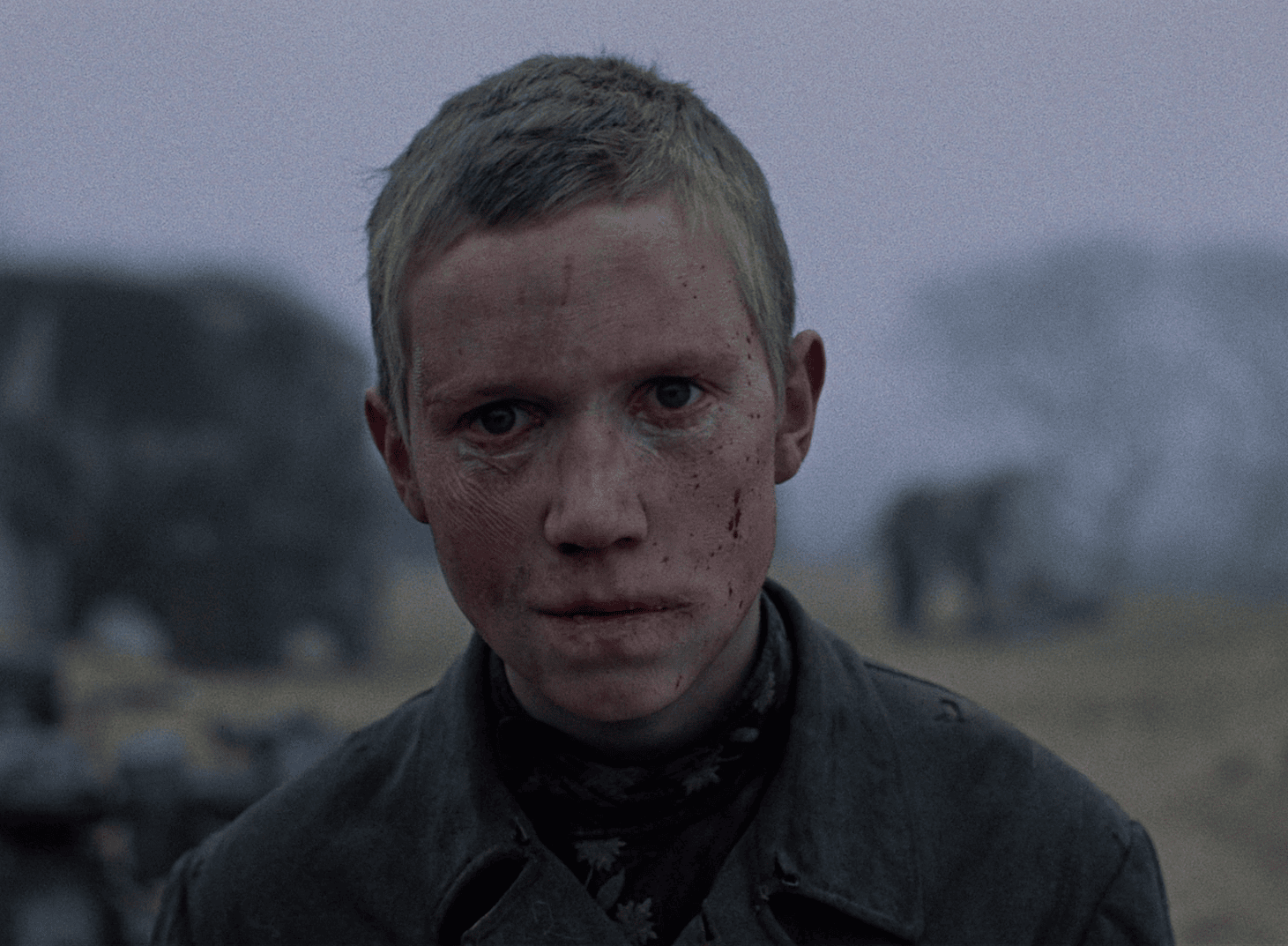

In the symphony of cinema, Elem Klimov’s Come and See is not a concerto; it is a primal scream that tears through the illusion of war and plunges you into its chaos. It doesn’t follow the grand, sweeping narratives of visionary generals and intoxicating battles. Instead, it burrows into the singed earth, into the heart of a young Belarusian boy named Flyora. Thrust into the partisan resistance, his journey isn’t one of heroic deeds but a merciless pantomime of survival. The adolescent recruit walks a tightrope with death, clinging to the tattered remnants of his childhood amidst the screeching of explosions and screams. This isn’t a film about conquering armies; it’s a gut-wrenching funeral for innocence, a haunting meditation on the human spirit’s resilience in the face of unimaginable hell.

If you can’t have any pity for me, then have pity for them.

In Come and See, the enemy isn’t a battalion of soldiers or a faceless dictator; It’s the abyss itself, gaping open and swallowing Flyora whole. His village, once a tapestry of laughter and folk songs, is wrenched apart by the belligerent Nazi onslaught, reduced to a divergent ensemble of shrapnel and wailing cries for mercy. His family, the bedrock of his world, becomes a casualty in the first act, setting the tone for the atrocities that lie ahead. The conflict here isn’t against a faceless foe but against the essence of childhood itself. Can innocence effortlessly balance on the precipice of annihilation? Director Elem Klimov doesn’t offer answers, only a haunting invitation to see with your own eyes as a young soul clings to his last memories of humanity.

Along with our primary protagonist in Florya, a young boy propelled into the maelstrom of the Eastern Front, we have Glasha, a beacon of fleeting hope in Florya’s sinking existence. She acts as a siren of survival, singing lullabies amidst the carnage, dancing in the rain-soaked battlefield, and guiding Flyora through the madness. But her own sanity dances on a razor’s edge, leaving you questioning if she is a savior or a fellow traveler heading towards a torturous demise. Kosach, the battle-hardened partisan leader, acts as a mirror to Florya’s future, a reflection of the cost of survival. Along with the local villagers, these characters represent the collective embodiment of a world forever changed by the trauma of war, each with faces etched with unimaginable suffering.

Klimov paints his canvas with the blood-red hues of tragedy and uncompromising despair. Cinematographer Alexey Rodionov’s camerawork is frantic yet meticulously calculated, mimicking the chaotic terror of a bombing raid. We see the world through Florya’s eyes, both figuratively and, at times, literally, the lens acting as his point of view. The natural light captures the desolation of the war-torn landscapes as shadows envelop devastated villages and flames shine on the deceased scattered across the ground. The camera becomes an unflinching witness, delving deep into the grotesque realities of war that linger on the faces of the haunted, etched with lines deeper than their years, capturing the hollowness in their gazes.

To hunt, the wolf walks on his paws.

The editing is something remarkable, forcing a dramatic pace within the plot, intermixing cruel and unrelenting violence with fleeting moments of beauty. Serene meadows explode into infernos. Comfortingly quaint villages give way to guttural screams of the dying. Klimov’s direction for lead editor Valeriya Belova forces you to confront the dissonance, the grating juxtaposition of life and death. There’s no reprieve, no purifying release; This is war, raw and unfiltered. The message is not lost on viewers, it’s one that grips you, holding you ransom until you acknowledge the extreme nature of a global armed conflict.

For a film with a single channel of audio (as opposed to a stereo mix), the sound design is remarkably horrifying and emotionally compelling within each scene’s context, relying heavily on substantial realism and ambient quietude rather than the complexity of a panoramic surround sound. Discordant strings scrape against the backdrop of explosions and screams of terror while whispered prayers beg for pity among the crackling of burning flesh. The silence following each atrocity is even more deafening, ringing with the absence of what once was, burrowing under your goose-bumped skin.

All the trouble starts with the kids. Your nation doesn’t deserve to exist. Some nations have no right to a future.

Florya’s clothing, once a token of his carefree youth, becomes ragged and bloodstained, mirroring the disintegration of his spirit. Props become talismans of loss. A broken harmonica, children’s toys amidst the charred debris, and other symbolic elements represent much more than meets the eye. As far as effects go, these are not Hollywood pyrotechnics but a visceral punch of realism. Bombs don’t just explode, they vaporize landscapes as the film’s crew sits behind small concrete slabs for protection. Animals in Come and See are actually killed, such as the cow that is shot, the nest of birds being stomped on, and the small loris being tortured by the partisans. The reactions from these animals, like the cow’s eye-rolling in a typewriter-like fashion after being shot, are all genuine, adding to the authenticity of the shots but raising important questions regarding ethics and the rights of animals in cinema. In the context of being an anti-war movie, these scenes force you to witness and truly feel the monstrous cost of human ambition while providing important symbolism toward the film’s narrative. The unhatched eggs, for example, act as a metaphor for Florya’s own youth being smashed before his eyes.

Come and See isn’t just a film; it’s an experience that I implore everyone to expose themselves to at least once. It’s not an easy film to watch, but its importance and cultural relevance in a world full of ongoing conflict cannot be understated. It’s a brutal assault on the senses, a relentless barrage of suffering guided by a child’s hand stained with blood and innocence. Come and See is a film that demands to be seen, felt, and discussed; a powerful reminder of the fragility of peace and the enduring cost of war. Elem Klimov doesn’t offer any concrete answers, only questions etched in fire and an open invitation for the audience to come and see the unfeigned reality of war for themselves. No wonder this is often considered one of the greatest and most significant anti-war films of all time.

Details

- IMDB | Letterboxd

- Released in 1985

- Directed by Elem Klimov